A free printable worksheet is available for this page. Click here or on the image below to download. Answers can be found on our worksheets page.

On this page we're going to discover how classification helps us to understand the relationships between species and also how different species evolved.

You can read the whole page to become an expert at animal classification (recommended!), or use the links below to jump straight to the facts you need.

Find out more about the animal kingdom at our main animals page.

You’ve probably heard of animal groups such as ‘mammals’ and ‘insects’. They are just two of the many groups that are used to categorize animals. All of the animals within groups such as these have certain things in common; they are ‘related’ to each other in some way.

Think of a typical mammal and a typical insect. Now try to list the physical similarities between them. Chances are the list won’t be very long; it’s clear that the two animals are not closely related.

Now repeat the exercise, either with two mammals or two insects. It’s likely that you’ll find it much easier to come up with a list of similarities between them.

Mammals and insects are very different animals. Sometimes the differences between animal groups aren’t quite so obvious. Crocodiles and alligators, for example, look similar, yet are in different families.

(A family is one type of animal group. You’ll meet others further down the page!)

Sometimes similarities between species are even more misleading. Think of a dolphin and a shark. Both live in the sea, both eat fish, and both look broadly similar to one another. Yet the dolphin is a mammal, and the shark is a fish.

All of the shark’s ancestors lived in the sea. The dolphin’s ancestors left the sea, evolved into mammals, then returned to the sea. (How amazing is that?)

If we hadn’t studied and classified mammals and fish we would never have known this.

Animal classification now uses sophisticated scientific methods to identify relationships between species.

Because the methods used to classify animals are continuously changing, the groups in which species are placed are sometimes changed. Occasionally, new species are identified!

For example, for many years elephants were classified into 2 species: African elephants and Asian elephants.

In 2010, DNA tests on African elephants revealed that there are actually 2 species of African elephant: African bush elephants and African forest elephants.

This means that there are now 3 species of elephant in total!

Finding out how different species are related to each other helps us to make sense of the animal kingdom. It also helps us to understand how animals evolved.

Animal classification is like putting together a huge ‘family tree’ containing every species – even those which are now extinct, such as dinosaurs.

The animal kingdom is a big group that contains every animal (including humans). The scientific name for the animal kingdom is Animalia.

Characteristics of animals include being able to move, and needing to consume other organisms (or the products of other organisms) for nourishment.

Species that don’t share these characteristics, such as plants and fungi, don’t belong in Animalia; they have their own kingdoms!

Classification doesn’t actually begin with kingdoms. As we’ll find out below, classification begins with groups called domains.

In classification, each large group of species can be divided into smaller groups. The species in each of the smaller groups are more like each other – more closely related to each other – than they are to the animals in the bigger group.

For example, the class Mammalia (mammals) is divided into several smaller groups, including the orders Carnivora (mammals who have the same, meat-eating, ancestors) and Artiodactyla (herbivorous mammals such as pigs, deer, hippos and cattle).

It doesn’t stop there. The species in a group such as Carnivora can be divided into even smaller groups. Smaller groups within Carnivora include the cat family (Felidae) and the dog family (Canidae).

The members of the cat family are more closely related to each other than they are to members of the dog family.

You can continue through the layers of classification by dividing the groups into smaller and smaller groups, each containing ever-more closely related animals, until you’re left with the individual species themselves.

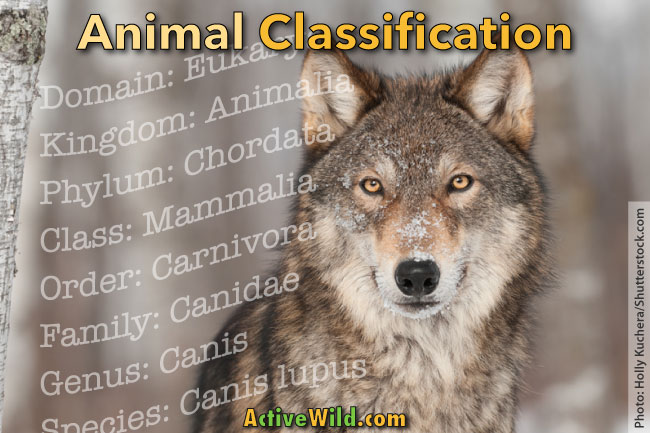

The layers of different groups are known as taxonomic ranks. There are 8 main taxonomic ranks, from domain down to species. They are: domain, kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species.

You can use the mnemonic* ‘daring king Phillip came over for good spaghetti’ to remember the taxonomic ranks (or perhaps you can think of your own phrase).

*A mnemonic is a way of remembering something.

We’re now going to take a closer look at each of the taxonomic ranks. We’ll use the gray wolf (Canis lupus) as an example. (UK spelling: grey wolf).

The first groups that living things are divided into are domains. There are only three domains: Eukarya, Bacteria and Archaea. Together they contain every single living thing.

Archaea and bacteria are groups of single-celled microorganisms. Although they resemble one another, there are several biochemical differences between archaea and bacteria.

Eukarya is the domain that contains fungi, plants, animals and protists. In fact, any organism whose cells have a nucleus is a Eukaryote.

The three domains were identified by microbiologist Carl Woese.

Domains are a relatively recent taxonomic rank. Before the technology that enabled us to identify the different domains existed, the highest taxonomic rank was kingdom.

Eukaryotes such as the gray wolf (an animal), sunflower (a plant) and fly agaric mushroom (a fungus) are clearly very different to each other. They are separated into different kingdoms.

There are either 5 or 6 kingdoms depending on where you go to school!

In the USA, the kingdoms are: Animalia (the animal kingdom), Plantae (the plant kingdom), Fungi, Protista, Archaea and Bacteria.

In other parts of the world, the kingdoms are: Animalia, Plantae, Fungi, Protista and Monera (which includes Archaea and Bacteria).

As we’ve already found, every animal is a member of Animalia, the animal kingdom.

Loosely speaking, members of the same phylum have the same overall body plan. For example, members of the animal phylum Chordata (chordates) all have a notochord – a flexible central rod.

There are actually additional ranks between the main taxonomic ranks. Under phylum is a rank called subphylum.

The subphylum Vertebrata is the group of animals that have backbones. Members of this group are known as vertebrates. ('Invertebrates' is a term used to describe all animals outside of this group.)

As we work our way down through the ranks, the animals in each group become more and more alike. The animals in a class such as Mammalia (mammals) all share certain characteristics. For example, all mammals have hair and are warm blooded (yes, even whales and dolphins have hair, although it's sometimes only present on very young animals).

Other examples of animal classes include: Arachnida (spiders & scorpions, etc.), Insecta (insects), Aves (birds) and Reptilia (snakes and lizards, etc.)

The animals in a class are split into smaller groups called orders. For example the class Mammalia (mammals) contains orders such as: Proboscidea (elephants), Sirenia (dugongs, manatees, and sea cows), Primates (apes and monkeys) and Rodentia (mice, rats and beavers, etc.)

Animal families are groups of related animals. The species in a family share many of the same characteristics. They are often similar in overall appearance.

Examples of animal families include Hominidae (great ape family), Corvidae (crow family) and Delphinidae (oceanic dolphin family).

Animals of the same genus are closely related to each other. They are usually similar in appearance and behavior.

When talking about more than one genus, use the plural, genera.

Examples of genera include: Felis (‘small’ cats such as the wildcat Felis silvestris and domestic cat Felis catus), Haliaeetus (sea eagles such as the bald eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus and white-tailed eagle Haliaeetus albicilla).

The genus to which an organism belongs makes up the first part of its scientific name. For example, the wildcat’s scientific name is Felis silvestris, therefore it is a member of the genus Felis.

Members of the same species are able to reproduce and create fertile offspring (i.e. their babies can also have babies of their own).

Some species can be further split into subspecies. Although subspecies are essentially the same type of animal, there may be slight differences between them, and they usually live in different areas. Subspecies of the same species are able to breed and create fertile offspring.

The table below shows how various well-known animals are classified.

| English Name | Gray wolf | Great White Shark | Ostrich | Nile crocodile | Red Eyed Tree Frog | Common Octopus | Man |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Domain | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya | Eukarya |

| Kingdom | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata | Chordata | Chordata | Chordata | Chordata | Mollusca | Chordata |

| Class | Mammalia (mammals) | Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish) | Aves (birds) | Reptilia (reptiles) | Amphibia (amphibians) | Cephalopoda (cephalopods) | Mammalia (mammals) |

| Order | Carnivora | Lamniformes | Struthioniformes | Crocodilia | Anura | Octopoda | Primates |

| Family | Canidae | Lamnidae | Struthionidae | Crocodylidae | Hylidae | Octopodidae | Hominidae |

| Genus | Canis | Carcharodon | Struthio | Crocodylus | Agalychnis | Octopus | Homo |

| Species | Canis lupus | Carcharodon carcharias | Struthio camelus | Crocodylus niloticus | Agalychnis callidryas | Octopus vulgaris | Homo sapiens |

Throughout history man has observed, named and compared animals and plants. The Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle classified species according to various characteristics, including whether they gave birth or laid eggs, or if they were warm or cold-blooded.

The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder wrote Naturalis Historia, a large work in which many plants were described. (It is also considered to be the first encyclopedia.)

Over the years, animal classification became more scientific. 16 th century Italian philosopher Andrea Cesalpino classified plants according to their fruits and seeds.

English naturalist John Ray published works on botany and zoology in the 17 th century. He classified species according to the similarities that he observed, and was the first person to offer a scientific definition of the word species.

Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) is known as the ‘father of modern taxonomy’. He popularized the binomial naming system, and introduced the use of kingdoms, classes, orders, genera and species. The Linnaean system is still in use today.

We hope that you have enjoyed this explanation of animal classification, and that you now know a little more about how the various groups of animals are related to each other.

Essentially, animal classification is about evolution. Finding out how animals are related to each other helps us to work out how species evolved.

It’s like creating a huge family tree that stretches back over millions and millions of years, right back to when life on Earth was nothing more than a few single-celled organisms floating in the sea.